A system of barrier islands existed off the central Belgian coast around 4,000 BC. Much like the Dutch Wadden Sea today, this long-lived coastal system comprised sandy islands fronting a mosaic of tidal flats and marshes. The once-famous island of Testerep appears to have been part of this system. It began to vanish from around AD 500, for reasons that remain unknown, while the currently existing Stroombank sand ridge started to form on the remains of the island’s sea-facing side from approximately AD 700. These findings are the result of the FWO Testerep Project, in which a multidisciplinary team from the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), KU Leuven and Howest University of Applied Sciences – Digital Arts & Entertainment (HOWEST DAE) have worked together over the past four years.

Artist impression of the barrier-island system in front of the central part of the Belgian Coast (4,000 BC) with a focus on the Testerep island as seen from the North Sea. (Ulco Glimmerveen)

Researchers of VLIZ, VUB and KULeuven reconstructed the landscape of the former central Belgian coast. The landscape must have looked like a barrier-island system during prehistoric times, much like the Dutch Wadden Sea today, and has changed drastically ever since.

Hidden channels and sandy deposits

The researchers focused in particular on Testerep, a former island in front of the Belgian coast that stretched between Nieuwpoort and Oostende. Their research reveals buried ancient tidal inlets – channels where seawater flows in and out with the tides – offshore of Nieuwpoort and Oostende. The inlets extend at least 3 km off Nieuwpoort and 4 km off Oostende, with widths of about 7.5 km and at least 3.3 km along the coast respectively. Dating evidence indicates that on the Nieuwpoort side, the preserved inlet was active from before 4500 BC until at least AD 500. On the Oostende side, the oldest age of activity is 5,500 BC, whereas it is less certain when this inlet became inactive. Since tidal inlets are channels that connect the sea to back-barrier bays, the presence of ancient inlets provides evidence that the Testerep island – nowadays eroded – was a barrier island, comparable to the barrier islands we know from the present day Dutch Wadden Sea.

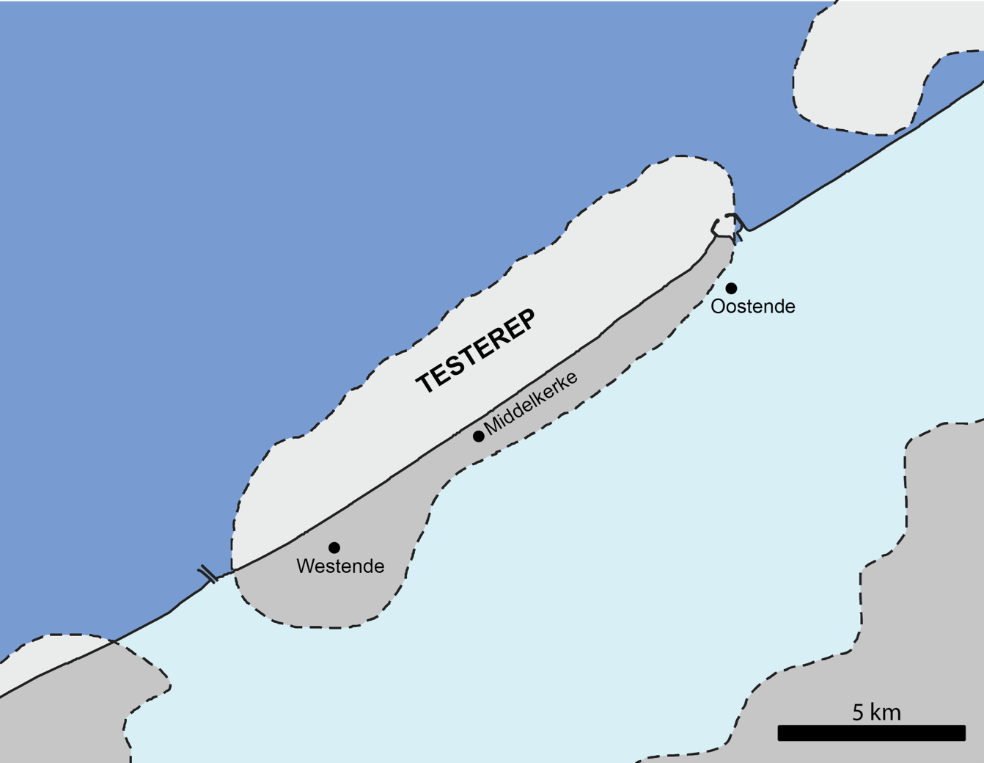

Further offshore, the researchers identified pockets of sandy coastal deposits, indicating a higher-energy depositional environment. These sediments are dated between 5,000 BC and AD 700 and are well preserved under the more recent deposits of the present-day Stroombank. The Stroombank is a sandbank, about two kilometers off the coast of Ostend, that runs from Westende to Klemskerke, where it merges into the beach. In total, it’s about 20 km long and roughly 1 km wide. The presence of sandy coastal deposits below the Stroombank is believed to point to the maximum offshore reach of the Testerep barrier island.

Quiet waters behind the sands

On the land side of the former Testerep barrier island, the team found well preserved peat deposits – the compacted remains of marsh plants – cut by ancient tidal channels. The presence of peat here points to low-energy back barrier settings similar to those landward of barrier islands today.

Taken together with geological evidence on land – dense networks of relict tidal channels, intertidal clays deposited in areas exposed at low tide, and widespread peat – the offshore findings reveal the presence of a barrier-island system, of which the Testerep island was one, off the central part of the Belgian coast. Dating evidence indicates this barrier system persisted for at least four millennia.

The landscape mirrors the modern Dutch Wadden Sea: a dynamic patchwork of barriers, tidal flats and saltmarshes shaped by the interplay of tides and waves. Whereas the underlying geology and hydrodynamical circumstances that created the Dutch Wadden islands and Testerep differ, the distribution of sedimentary environments makes the ancient Belgian coast a strong analogue for today’s Wadden landscapes.

As Testerep waned, the Stroombank took shape

Between the 3rd and 8th century AD, the offshore reach of the Testerep barrier island started eroding. Although the cause of Testerep’s disappearance remains unresolved, possible drivers range from changing storminess and sea-level trends to shifts in sediment supply due to human activities. Around AD 700, the Stroombank began to take shape on top of the disappearing island, growing gradually parallel to the present-day coast. The geological research also shows clear signs of coastal erosion as early as about AD 1200, visible where deposits of the former tidal inlets at Nieuwpoort were cut back.

Soetkin Vervust, coördinator van het Testerep-project:

“Our results point to a Belgian coastline that likely included sandy barrier islands for thousands of years, with Testerep as one of them. By imaging what lies beneath the seabed and dating the sands and peats directly, we can start to fill in the missing pages of the coast’s history – while acknowledging what we still don’t know.”

Map reconstructing the likely coastline of Testerep around 4,000 BC. The current coastline is shown as a black line.

Peering beneath the seafloor: sound, cores and light-based dating

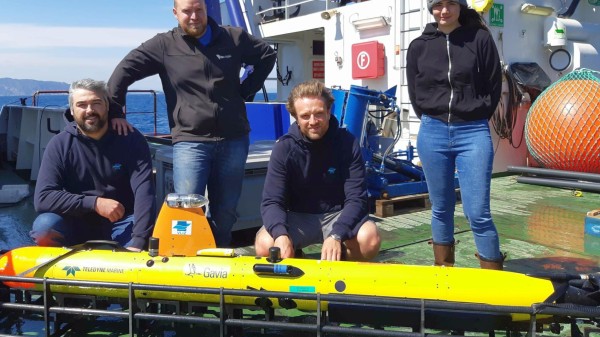

The team of marine geophysicists, archeologists and modelers used high-resolution acoustic imaging (sound-based seafloor scanning), sediment cores (layered samples extracted from the seabed), radiocarbon and luminescence dating (a light-based dating technique that reveals when sand grains were last exposed to daylight) to study the former Testerep island and the Stroombank.

About the Testerep project

This study formed part of ‘TESTEREP: The evolution of the Flemish coastal landscape (5000 BP–now) – Testerep reconstructed for policymakers and the general public’, a Strategic Basic Research (SBO) project funded by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) that ran from 1 October 2021 to 30 September 2025. The project focused on the former Testerep island between Nieuwpoort and Oostende, where the southern sector became present-day polders and beach, while the northern part – including medieval Ostend – was lost to the sea. Researchers from VUB, VLIZ and KU Leuven integrated existing records of natural features (such as tidal channels) and human features (such as dikes) with new land and offshore data; HOWEST DAE translated the science into visualisations and communication products.

On Wednesday 5 November 2025, the project results were presented to various stakeholders from policy and industry, at Silt in Middelkerke. The project partners looked back at what the project taught us about how our coast took shape, gave a behind-the-scenes look at the research, and talked with stakeholders involved in the different outreach and valorisation trajectories.