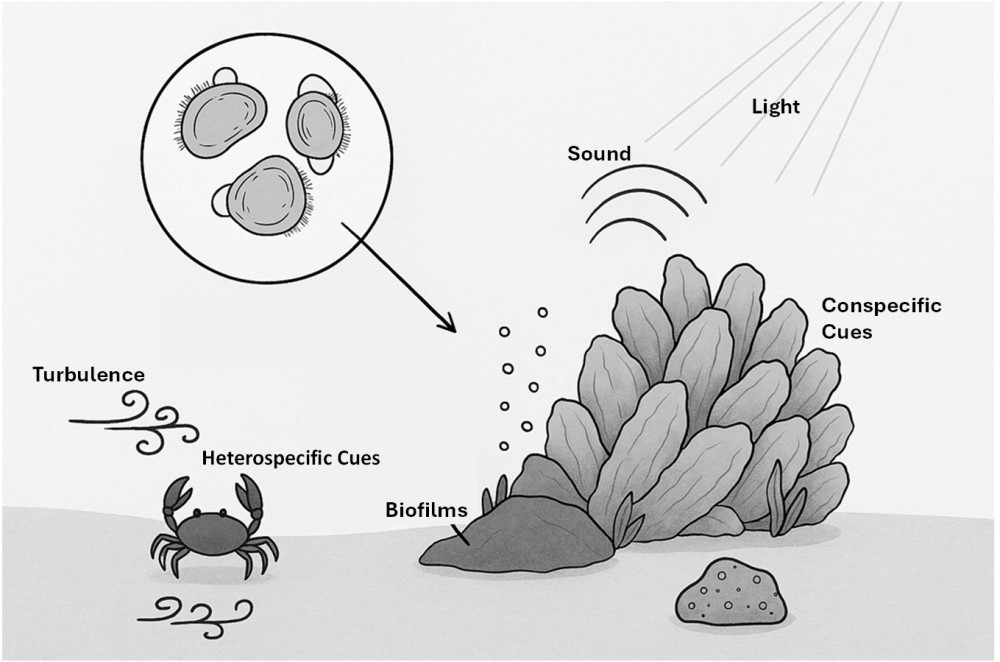

For young oysters, finding the right place to settle is literally a matter of life and death. Their transition from free-swimming larvae to permanently attached adults is guided by a wide range of environmental cues. In her recently defended doctoral research, Sarah Schmidlin demonstrates that the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) uses not only chemical signals but also underwater sounds and microscopic surface textures to select the best habitat. Moreover, larvae appear capable of switching intelligently between sometimes conflicting signals. These insights not only deepen our understanding of their ecology, but can also contribute to more effective restoration of endangered shellfish reefs and to sustainable aquaculture practices.

Settlement and metamorphosis are crucial stages in the life cycle of reef-forming bivalves such as mussels and oysters. During settlement, larvae descend from the water column and temporarily attach to a surface. Only when they undergo metamorphosis — an irreversible physiological transformation — does their sedentary adult life begin.

In her doctoral dissertation ‘Early colonization by marine ecosystem engineers’, Sarah Schmidlin experimentally investigated how larvae respond to a variety of cues. She found that larvae of the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) not only recognize chemical signals from conspecifics and biofilms, but are also sensitive to physical cues such as sound and micro-topography. Acoustic signals from existing oyster reefs were found to stimulate metamorphosis, while microscopic surface textures on concrete helped larvae decide where to settle.

Importantly, larvae never interpret just one cue in isolation. In underwater landscapes full of overlapping and sometimes contradictory stimuli, they weigh multiple signals at once. A strong positive substrate cue, for instance, may cause them to ignore negative chemical cues in the water. These “decision-making strategies” increase their chances of finding a viable habitat.

The implications are significant: by better understanding how larvae integrate different signals, we can design artificial reefs that are more attractive for settlement. This knowledge offers a valuable lever for ecosystem restoration and sustainable aquaculture — particularly now that shellfish reefs worldwide are under pressure.

PhD and supervision

Sarah Schmidlin’s PhD was carried out at the Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ) and Ghent University (Department of Marine Biology), under the supervision of Prof. Pascal Hablützel (VLIZ), Prof. Jan Mees (VLIZ & UGent), and Dr. Pauline Kamermans (Wageningen University). The examination committee included Prof. Ann Vanreusel (UGent), Prof. Annelies Declercq (UGent), Prof. Elisabeth Williams (University of Exeter), Dr. Nadjejda Espinel Velasco (University of Gothenburg), and Dr. Carl Van Colen (UGent).

With this work, Sarah Schmidlin makes an important contribution to the fundamental understanding of larval ecology, as well as to the development of practical applications for reef restoration and sustainable shellfish aquaculture. VLIZ and Ghent University warmly congratulate her on earning her doctorate.

Reference

Schmidlin, S. (2025). Early colonization by marine ecosystem engineers: settlement and metamorphosis of the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas) in a complex sensory landscape of chemical, tactile and sound cues. PhD Thesis. Ghent University, Faculty of Sciences, Marine Biology/Flanders Marine Institute (VLIZ): Gent, Oostende. 222 pp.