Number of alien species over time

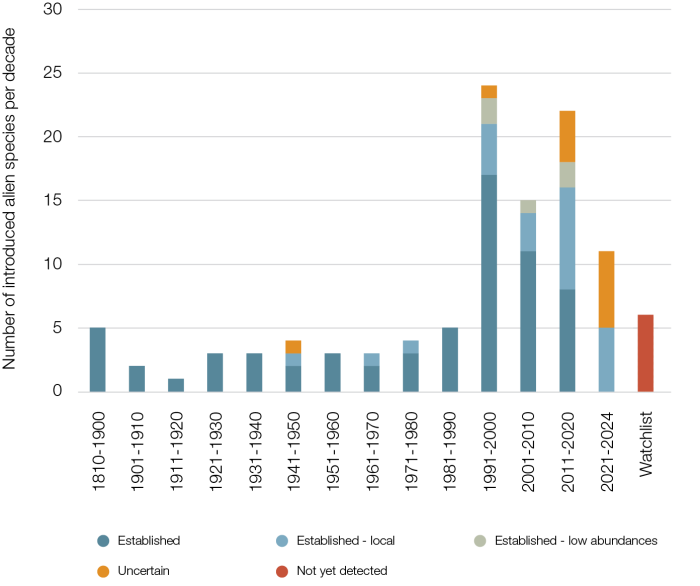

As of 2024, 105 introduced alien species have been confirmed in the Belgian part of the North Sea and adjacent estuaries (figure 2). Additionally, six so-called ‘Watchlist species’ have been identified, which require increased vigilance as they have been observed near the Belgian border (Wester Scheldt, Eastern Scheldt, Opal Coast) but have not yet been found in Belgian territory. This marks a significant increase compared to the 2020 version of this list, when the count stood at 79 introduced alien species. For the 32 newly included species, 2 were introduced between 1991-2000, 14 between 2011-2020, 11 between 2021-2024, and 5 have been observed near the border but not yet in Belgium (the sixth watchlist species was already included in the previous version).

Figure 2: The number of newly introduced alien species in the study area per decade (species introduced before 1901 are grouped together), categorised by species groups. The line graph cumulatively shows the total number of introduced alien species at a given time. The gray area chart displays the number of species records in GBIF for the Kingdom 'Animalia' in the Belgian part of the North Sea and adjacent estuaries, serving as an indicator of the intensity of biological sampling.

Five introduced alien species have been present in the Belgian territory since the 19th century. The number of new introductions showed a steady increase throughout the 20th century (up to 1990), with five or fewer new species per decade. By 1990, 33 introduced alien species were known in the study area. However, between 1991 and 2000, there was a sudden spike in the number of introductions, with 24 new species recorded in just ten years. This explosive increase was followed by 15 new species between 2001 and 2010 and another 22 between 2011 and 2020. In the short period from 2021 to 2024, 11 new species have already been observed (figure 2). In contrast to the species found before 1990, most of which are considered generally established (88%), a significantly smaller proportion of the species found in Belgium after 1990 have become widely established. Among these species, 50% have become generally established, 28% are locally established in very specific (isolated) areas, and 7% are characterised by very low abundance but a confirmed presence. Additionally, for 15% of the species, it remains uncertain whether they have established themselves (figure 3).

Figure 3: The number of newly introduced alien species in the study area per decade (species introduced before 1901 are grouped together), categorised by the extent to which the species has or has not been able to establish itself.

If the 111 species are considered together (including the 6 ‘Watchlist’ species), it can be stated that arthropods dominate, accounting for 34% of the total number of identified introduced alien species. This is a diverse group, including crabs, copepods, amphipods, isopods, sea spiders, barnacles, and shrimps. This group is followed at a distance by mollusks (17%), worms (12%), and algae and seaweeds (12%). The remaining groups are tunicates (5%), cnidarians (5%), bryozoans (5%), fish (5%), vascular plants (2%), protozoa (1%), rotifers (1%), comb jellies (1%), and sponges (1%) (figure 2). It should be noted, however, that the analysis of zooplankton and phytoplankton in Belgian waters has only been conducted systematically since 2014 and 2017, respectively (VLIZ - LifeWatch Belgium). While this data collection presents opportunities for detecting potential introduced alien species within these groups, this has not yet been a focus in recent years, so these groups may be underrepresented in the current publication. Compared to benthic habitats, research into pelagic habitats is still in its early stages, and therefore, there is less concrete information available (Belgian State, 2022). Moreover, the limited past attention to the pelagic zone also makes it more challenging to determine which species are truly non-native.

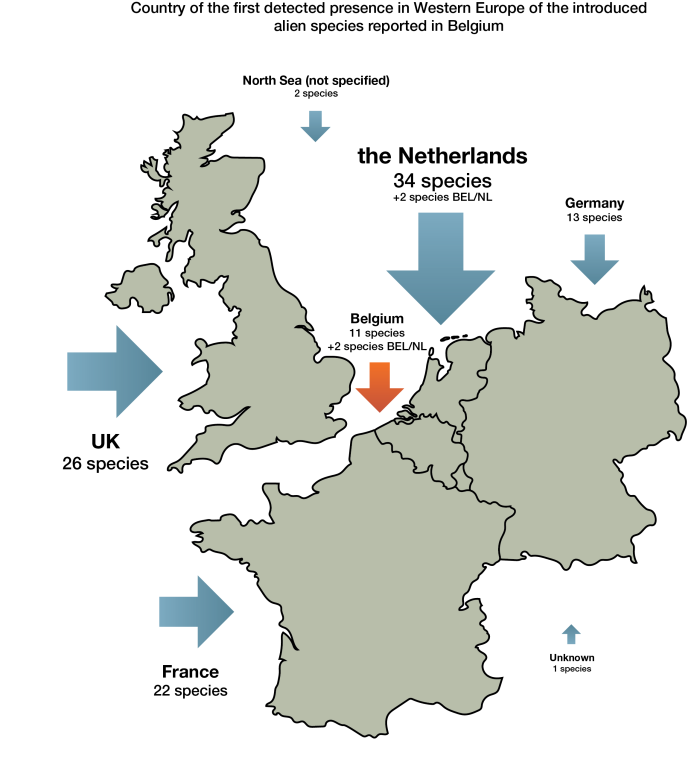

Based on the observation data, it can be stated that for 13 of the 111 identified species (12%), the ‘primary’ transport to Western Europe occurred via Belgium (figure 4). The importance of maritime transport and port activities in relation to these specific introductions becomes clear when studying the potential introduction vectors. For all 13 species, shipping played a potential role in spreading beyond the origin area, with ballast water transport identified as a potential vector for 10 of the 13 species and biofouling on ship hulls for 7 of the 13 species. Possible import via aquaculture activities applies to 3 of the 13 species, and intentional release as a potential introduction pathway is noted for 1 organism. In addition to primary introductions, ports and aquaculture activities also played a significant role in the secondary spread of introduced alien species. In fact, 88% of the introduced alien species found in (or near) Belgium were first recorded in one of the neighboring countries: 31% were first reported in the Netherlands, 23% in the United Kingdom, 20% in France, 12% in Germany, 2% in the North Sea region (not further specified), and for 1%, there is uncertainty regarding the location of the first introduction in Western Europe (figure 4).

Figure 4: Visualisation of the country of the first detected presence in Western Europe of introduced alien species found in (or near) Belgium.

As outlined above, it is widely known that international shipping plays a major role in the unintentional spread of organisms beyond their native range. The fact that the Flemish seaports are located along one of the busiest maritime shipping routes increases the risk of new introductions via maritime transport. The sharp increase in the number of introduced alien species since the 1990s could seemingly be linked to the rise in shipping traffic to the Flemish seaports, which, in terms of cargo throughput (tonnage), was twice as high in 2019 as in 1990 and nearly tripled compared to 1980 (Merckx, 2020). However, the number of shipping movements decreased by 15% during the same period (1980-2019), so the increased cargo throughput is a result of the growing size of the vessels. The ‘intercontinental’ nature of shipping (e.g., in the Port of Antwerp) has notably increased since 1990, with maritime transport to and from Asia (in volume) increasing sevenfold over the last three decades, and cargo transport to and from America and Africa doubling (Merckx, personal communication). These large vessels often visit multiple Atlantic/North Sea ports and can thus contribute to both the primary and secondary introduction of new species.

The International convention for the control and management of ships' ballast water and sediments (Ballast Water Convention – BWM Convention) aims at the international level to prevent the spread of invasive introduced alien species from one region to another by establishing standards and procedures for the management and control of ballast water and sediments in ships. The BWM Convention was adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2004 but only came into force on September 8, 2017. In its first phase (the 'D-1 standard'), it required all seagoing ships equipped with ballast tanks and larger than 400 gross tonnage (with a few exceptions) to exchange 95% of their ballast water well offshore. Since September 8, 2024, the 'D-2 standard' has been in effect. The D-2 standard concerns approved ballast water treatment systems and sets the maximum amount of viable organisms that may be discharged into the sea. As a result, ships engaged in international voyages must remove or neutralise aquatic organisms and pathogens from their ballast water before discharging it at a new location. Given the recent implementation of the final phase, it is not yet possible to evaluate the effectiveness of the measure. However, it is known that for 57% of the marine introduced alien species encountered in Belgium after 2000, ballast water transport is considered a potential introduction vector. Specifically, ballast water may have played a role in the introduction of 5 out of 8 worms, 12 out of 17 arthropods, 3 out of 3 fish, 6 out of 8 mollusks, 1 out of 1 comb jelly, and 1 out of 1 cnidarian. For the worms, a strong increase in the number of introduced species has been observed after 2010, evolving from 4 species pre-2010 to 13 by 2024. It should be noted that all the worms first encountered post-2010 exhibit a cryptic lifestyle or are characterised by difficult species identification, which does not rule out the possibility of earlier introductions.

This seamlessly brings us to another possible reason for the sharp increase in the number of introduced alien species after 1990: the higher frequency of biological sampling and the development of monitoring campaigns at sea, whether or not under European regulations and international or regional obligations. For example, the number of species records within the kingdom ‘Animalia’ in GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) for the study area shows an increase since the 1970s and a rapid acceleration starting from 1990 (figure 2). This data suggests more intensive biological sampling in the study area, which also increases the chances of discovering new species. Additionally, the implementation of environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques for monitoring can also reveal new species that are characterised by low abundance, cryptic presence, or complex species identification (cf. the worms). For example, the potential presence of Notocomplana koreana near Vlissingen (Western Scheldt) was already suggested in 2017 based on eDNA analyses, although the species has not yet been physically identified there. However, this flatworm was found three years later in the Veerse Meer and the Grevelingenmeer.

Native regions

The native regions of the introduced alien species in the study area are very diverse. Some species occur naturally in multiple regions, while there is uncertainty about the natural distribution area for 13% of the species (so-called cryptogenic species). As a result, the total number of species across the native regions is greater than the actual number of species (figure 5).

The main areas of origin of the marine introduced alien species in (and near) Belgium are the Northwest Pacific (29%) and Northwest Atlantic (23%) regions, together accounting for over half of the marine introduced alien species in our area (figure 5). In total, the Pacific region is the origin of 45% of the marine introduced alien species found in Belgium. The Atlantic area accounts for 28%, the Mediterranean region, Pontocaspian region, and Indian Ocean each account for 4%. The importance of the different areas of origin for the introduced alien species found here varies depending on the transport vector. In the case of aquaculture as a (potential) introduction vector, the significance of the Northwest Pacific region rises to 45%, while the share of species from the Northwest Atlantic Ocean is only 11%. For shipping, these percentages are 27% and 23%, respectively. When introductions are linked to canal digging, 60% of the species originate from the Pontocaspian region and 30% from the Mediterranean region.

Additionally, there are clear differences between the various native regions at the level of species groups. While algae and seaweeds make up the main species group from the Northwest Pacific, accounting for 27% of the introductions from this region (along with arthropods, also 27%), no algae or seaweed introduced to Belgium originates from the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. From this latter region, mollusks are the dominant group (32%), whereas they only account for 12% of species from the Northwest Pacific region. Across all regions, arthropods consistently dominate.

Figure 5: The number of introduced alien species in the study area, categorised by native region. The sum of the different regions exceeds the actual number of species because certain organisms are linked to multiple 'potential' native regions.

Introduction pathways

Marine species can be introduced outside their native range in various ways due to human activities. The predominant ‘potential’ introduction vectors for the introduced alien species in the study area are shipping (83 species)—mainly through ballast water (56 species) and hull fouling (53 species)—and aquaculture/live import (49 species) (figures 6 and 7). The number of detected introduced alien species linked to these transport vectors has significantly increased since the 1990s. Additionally, introductions also occurred through the construction of canals between regions that were initially separated by physical barriers, facilitating the further spread of species outside their native range. Introduced alien species can also be intentionally introduced through the release or planting of alien species. This was the case, for example, with the established non-native vascular plants in the study area (figure 6).

Figure 6: Overview of introduction pathways over time. The sum across the decades is higher than the actual number of species because there is often uncertainty about the primary introduction vector or because some species were introduced multiple times, separately and through different pathways, from the native region.

Depending on the native region, the significance of a particular vector varies. For example, all exotics from the Pontocaspian region (Black Sea, Caspian Sea) were introduced due to the construction of canals between the Black Sea and Western Europe. Through this method, organisms were able to spread westward via connected rivers or via inland vessels. Introductions from the Atlantic Ocean, on the other hand, mostly occurred through ballast water transport, while from the Pacific Ocean, both shipping and aquaculture/live import played a significant role.

Despite the increase in international shipping traffic in recent decades, this vector also played a significant role (relatively speaking) in the spread of species beyond their native region during the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries (figure 6). Both ballast water transport and hull fouling have been long-standing mechanisms for the spread of species. The BWM Convention (see also Introduced alien species: impact and overarching policy framework and Policy and legislation) aims to reduce the spread of species through ballast water within the context of international maritime transport.

Figure 7: Overview of the possible introduction pathways at a higher taxonomic level. The sum of the different species groups exceeds the actual number of species because there is often uncertainty about the primary introduction vector or because some species were introduced multiple times, separately and through different pathways, from the native region.