Turtles

Hawksbill turtle. Hawksbill turtle.

© David Obura

|

Green turtles mating. Green turtles mating.

© David Obura

|

|

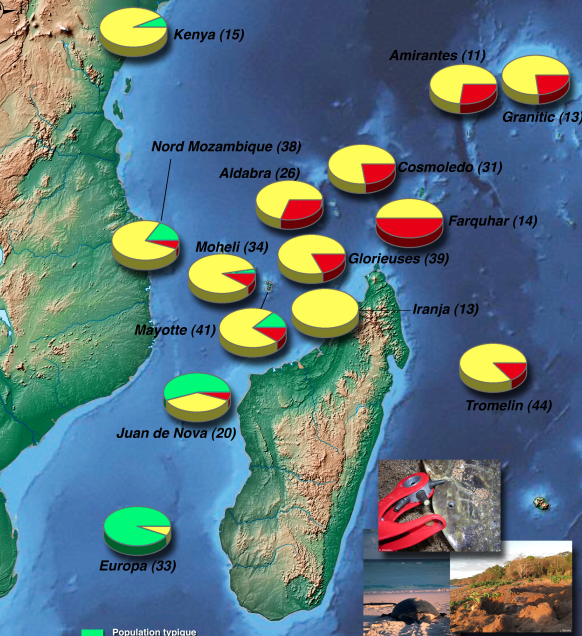

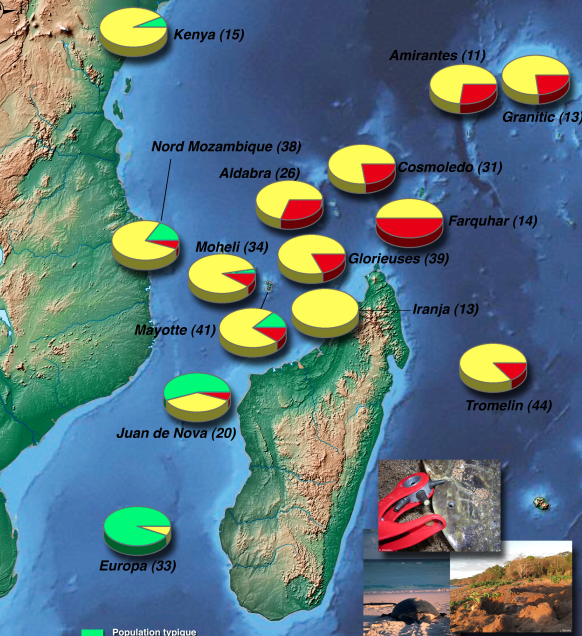

Green turtle genetic structure in the WIO. Green turtle genetic structure in the WIO.

© Kelonia, Reunion

|

Five out of seven species of marine turtle worldwide occur in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO): Green turtle Chelonia mydas, Hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata, Loggerhead Caretta caretta, Leatherback Dermochelys coriacea, and Olive Ridley Lepidochelys olivacea. The most abundant species in the WIO is the Green Turtle, and the second most common is the Hawksbill. On the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species all are currently listed either as Critically Endangered (hawksbill, leatherback) or Endangered.

The complicated life cycles of sea turtles require them to utilize a variety of habitats. Eggs are laid and incubate in beach sand, but post-hatchlings are pelagic and inhabit the surface waters of convergence zones and major gyre systems throughout tropical and temperate oceans. These juvenile stages migrate with ocean currents over 1000s of kilometers. Most adult turtles also migrate over such distances, though post-nesting hawksbills in the Seychelles they do not migrate as far as do adult green or loggerhead turtles. The feeding grounds of the bottom-feeding sea turtles include seagrass, coral reef, sand and mud flats, and mangrove ecosystems, while the pelagic leatherback feeds in oceanic surface waters of tropical, temperate, and even polar seas. Thus, the state of turtle populations is a good indicator of the overall health of coastal and marine ecosystems. Turtles may also be crucial for the functioning of healthy marine ecosystems; findings from the Caribbean suggest that the demise of the macro-herbivorous green turtles following European colonization had significant effects as few other species feed on seagrasses.

There has been extensive sea turtle research since the early 1990s in the region, but this information is still relatively scattered and not always standardized. Nevertheless, sea turtle information has been a backbone of the two subregional ecoregional planning exercises for mainland East Africa (WWF 2004) and the islands (RAMP-COI, unpublished). There is however a need for more specific sea turtle data particularly on feeding, breeding, juvenile routes and adult migratory routes in the WIO.

Genetic research has shown that there is mixing between the Atlantic Green turtle and those of the Mozambique channel, and the south population of green turtles in the WIO (central Mozambique channel and southwards). Green turtles in the north of the channel and northwards are distinct, and there may be a distinct Seychelles population as well, with links to the Southeast Asian region. Interestingly, green turtles found between the islands of Europa and Juan De Nova were from both southern and northern genetic populations. The genetic differences could result from oceanographic features that affect the movement of the juveniles, suggesting a separation between the northern and southern parts of the Mozambique channel.

Species-specific information, on sea turtles is provided below, though there are still significant gaps, particularly for parts of Madagascar and Mozambique.

Green turtles

|

|

Area |

Importance |

|

Mozambique channel |

Used by all 5 species, genetic differentiation likely due to oceanography of the channel, separating northern and southern populations. |

|

Isles Eparses, especially Europa, Glorieuse Tromelin

|

Females nesting per annum: Europa up to 10,000; Grande Glorieuse 3000; Tromelin 1500, Juan de Nova <100. Annual trends in the number of nests over the last 20 years are positive for Europa, stable for Tromelin. |

|

Comoros, especially Moheli |

Up to 70,000 nesting females a year, and development habitat for the juveniles. |

|

Mayotte |

Up to 5000 nesting females a year, key feeding grounds and important to the juveniles.

|

|

Seychelles |

Up to 10,000 female green turtles nest annually in Seychelles, predominantly in the southern islands--esp. Aldabra, Assumption, Cosmoledo, Astove and Farquhar. The species has become rare in the inner islands and Amirantes due to continuing exploitation.

The Aldabra (WHS) green turtle population protected since 1968 has increased by 500-800% since 1968 and now numbers approximately 5000 females nesting annually and the population is increasing exponentially. Important feeding grounds for green turtles are adjacent to virtually all islands of Seychelles. Active conservation programmes involving nesting green turtles are underway in the Amirantes Group at Alphonse/St. Francois atolls, D’Arros/St. Joseph atoll, and Desroches, at a number of the inner islands (see following discussion of hawksbills). |

|

Bazaruto |

Nesting, feeding grounds and important for the juveniles.

|

|

Quirimbas - Mnazi Bay |

Important nesting and feeding grounds, up to 200 nests per year. |

|

Mafia – Rufiji |

Key feeding grounds and some key nesting sites.

|

|

Kiunga, Kenya |

Key feeding and nesting area with up to 130 nests a year.

|

Hawksbill turtles

|

|

Area |

Importance |

|

Saya de Malha/Banks |

Feeding ground but there is limited information available. |

|

Mozambique channel

|

Migratory route. |

|

Isles Eparses |

Juan de Nova - up to 50 nesting females a year.

Europa – important as development habitat (mangrove) for juveniles.

|

|

Mayotte |

Up to 5000 nesting females a year, key feeding grounds and important to the juveniles.

|

|

Seychelles |

Most hawksbill nesting in the WIO occurs in the inner Islands (on the Seychelles Bank) & the Amirantes Group. Approximately 2,000 females are estimated to nest annually in Seychelles. Satellite telemetry indicates the Seychelles Bank is the primary feeding ground for hawksbills nesting in the Granitic Seychelles, but hawksbills feed in habitat <60 m deep throughout Seychelles and important feeding grounds for immature hawksbills are found adjacent to virtually all islands in Seychelles. All sea turtles are legally protected in Seychelles and active conservation programmes are underway at nearly all of the inner islands (especially Aride, Bird, Cousin, Cousine, Curieuse, Denis, Fregate, North, Silhouette, Ste. Anne, and parts of Mahé and Praslin) and in the Amirantes group at Alphonse/St. Francois atolls, D’Arros/St. Joseph atoll, and Desroches, as well as at Aldabra atoll in the southern islands. |

|

Bazaruto |

Nesting, feeding grounds and important for the juveniles.

|

|

Quirimbas - Mnazi Bay |

Important nesting and feeding grounds. |

|

Mafia – Rufiji |

Feeding grounds and some key nesting sites however there is limited information available.

|

|

Kiunga |

Feeding and nesting area with up to 10 nests a year however there is limited information available.

|

|

N. Madagascar |

Very limited information is available, though nesting is present in many locations, e.g. Nosy Iranja.

|

Loggerhead and leatherback turtles

- Known important nesting areas include the Maputo Bay – Machangulo Complex, iSimangaliso in Kwazulu-Natal (World Heritage Site), the Bazaruto archipelago and South East Madagascar.

- Foraging populations of both species are found throughout the Seychelles as well as La Réunion and the Scattered islands. East African coast (Mozambique + Tanzania + Kenya) are important feeding grounds for the loggerhead.

Olive Ridley – There is limited information on the Olive Ridley in the WIO especially on specific nesting, feeding grounds and their juvenile movements. Olive ridleys have been recorded in the waters of the inner islands of Seychelles and in the Mascarenes, and a few nest reports have been provided from Kiunga Marine National Reserve and Malindi in Kenya.

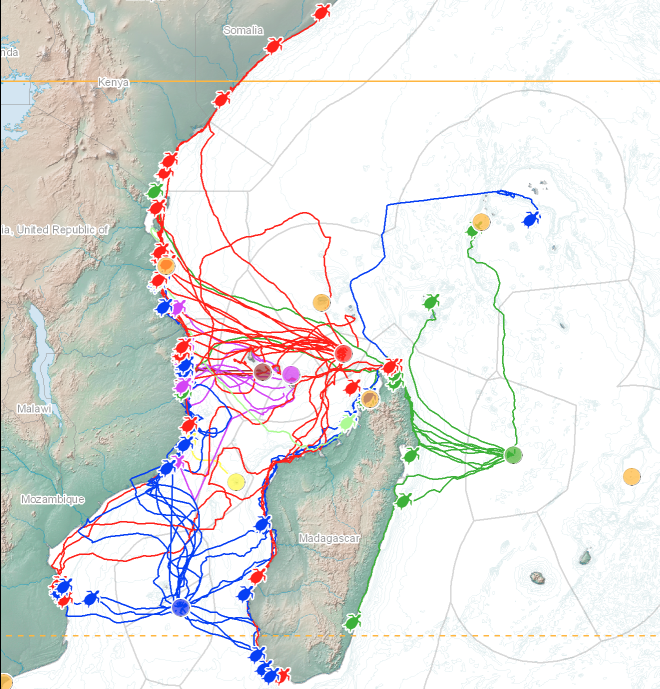

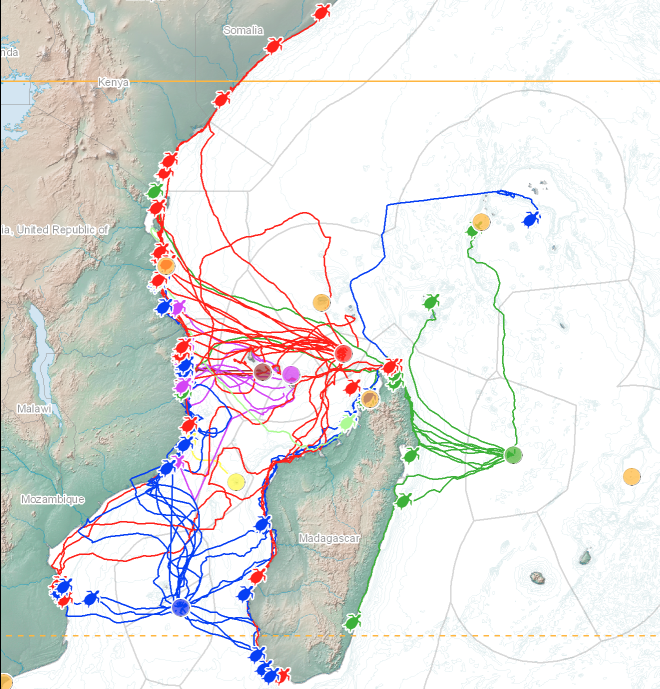

Green turtle migration routes. Green turtle migration routes.

© Kelonia, Reunion

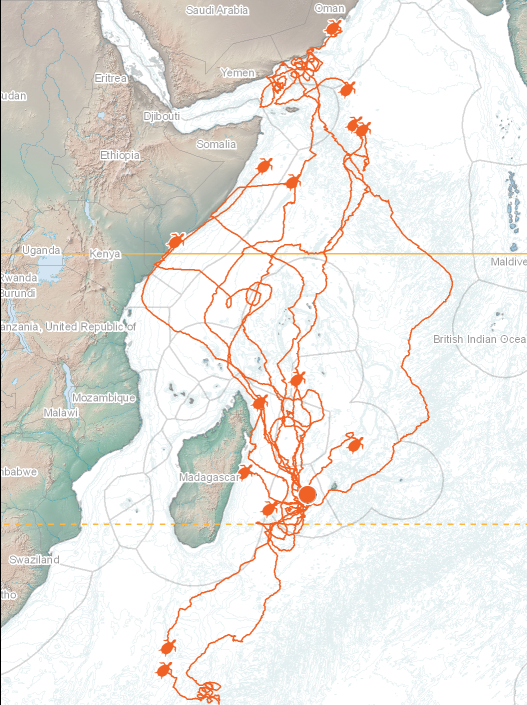

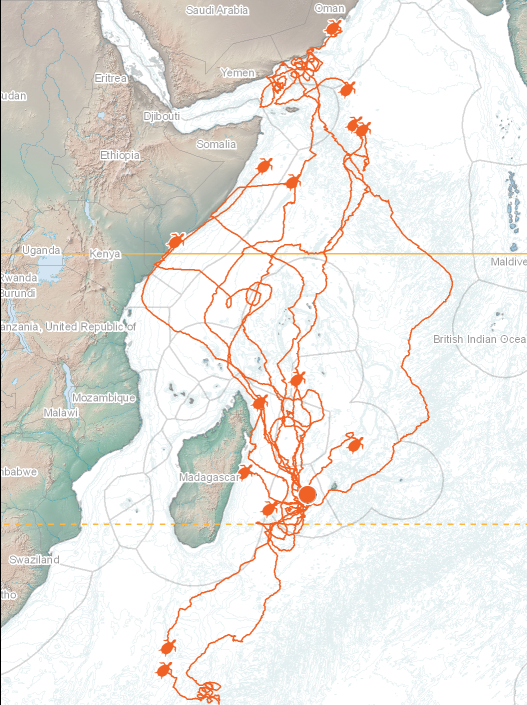

Loggerhead turtle migration. Loggerhead turtle migration.

© Kelonia, Reunion

|

Turtles are vulnerable to being caught in fishing nets, such as this one set in a channel mouth. Turtles are vulnerable to being caught in fishing nets, such as this one set in a channel mouth.

© David Obura

|

Threats - Some of the threats facing marine turtles in the WIO include: exploitation for food (meat and eggs), oil, leather and ornamentation; mortality associated with incidental capture in fisheries; marine and land-based pollution; and disruption of essential nesting and feeding sites. Some of these threats have been going on for centuries as turtles have long been a resource of economic and cultural significance to people living in the region. Turtle meat and eggs provided protein to coastal residents, and the calipee (dried cartilage used to make turtle soup) and meat from green turtles and shell from hawksbills were exported to foreign markets in Europe and Asia. In some locations (for example, South Africa, Kenya, Seychelles, Mayotte and Madagascar) turtles also generate income as a tourism attraction.

Until the mid-to-late 1900s direct take of turtles and their eggs posed the greatest danger to their long-term survival. While this remains an enormous problem in many areas, indirect threats are growing in importance, particularly incidental bycatch in artisanal and commercial fishing gear, and loss of nesting and foraging habitats due to coastal development, pollution, and erosion resulting from poor coastal management and sea level rise. Marine ecosystems are disrupted by overexploitation, mechanical damage, pollution of all kinds and land-based runoff as well as by temperature rise associated with global warming and climate change.

Conservation of sea turtles - According to the Sodwana Declaration (IUCN, 1996) “only a few of the discrete populations in the region are stable or growing; three of the populations are becoming extinct; most populations are either in decline or have not yet begun to recover from centuries of irrational use”. Sea turtle conservation and management provide numerous challenges. Saving sea turtles requires the protection of these ecosystems on which we all depend on both small and large scales. Moreover, sea turtles are highly migratory, and individual animals may travel tens of thousands of kilometers in their lifetimes, spending various lengths of time in the open sea, and in territorial waters of multiple states. Conserving sea turtles thus also mandates that people cooperate internationally and regionally. Also, although such threats are fairly well recognised they are not as well documented, and spatial and temporal overviews of threats generated from specific data sources are lacking.

Today international agreements, most importantly CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), prohibit international trade in sea turtles. Two regional instruments relevant to sea turtle conservation in the WIO include the Sodwana Declaration, which provides a comprehensive “shopping list” of priority actions and strategies in various domains, but was not set in a way to hold Governments and other partners accountable for actions, and the Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Marine Turtles and their Habitats of the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia (IOSEA), adopted in 2001 under the auspices of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). However, this too, is non-binding, but undertakes a suite of activities coordinated from a secretariat co-located with UNEP in Bangkok, Thailand. Under these programmes, several meetings have been hosted in the WIO over the last two decades, all calling for regional cooperation among countries to manage sea turtles as a shared stock, though WIO countries are still conducting turtle conservation and management largely in isolation. The World Heritage Convention offers a particularly powerful complement to this suite of regional instruments.

Key References - Allen et al. (2010); Bourjea et al. (2006); Bourjea et al. (2007); Frazier1984; Lauret-Stepler et al. (2007); Mortimer (2004); Mortimer & Balazs (1999); Mortimer 1984; Mortimer 1988; Mortimer and Bresson (1999); Mortimer et al. (2011); Remie and Mortimer (2007); WWF (2004). --> References |

Hawksbill turtle.

Hawksbill turtle. Green turtles mating.

Green turtles mating. Green turtle genetic structure in the WIO.

Green turtle genetic structure in the WIO. Green turtle migration routes.

Green turtle migration routes.  Loggerhead turtle migration.

Loggerhead turtle migration.  Turtles are vulnerable to being caught in fishing nets, such as this one set in a channel mouth.

Turtles are vulnerable to being caught in fishing nets, such as this one set in a channel mouth.