|

|

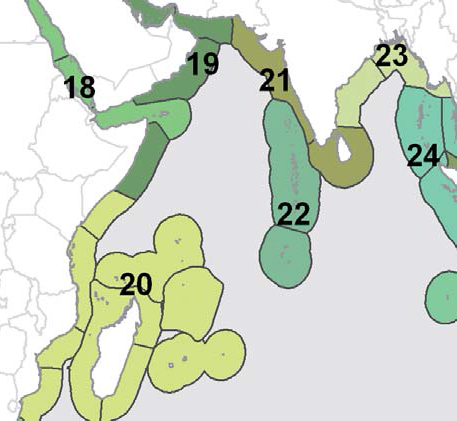

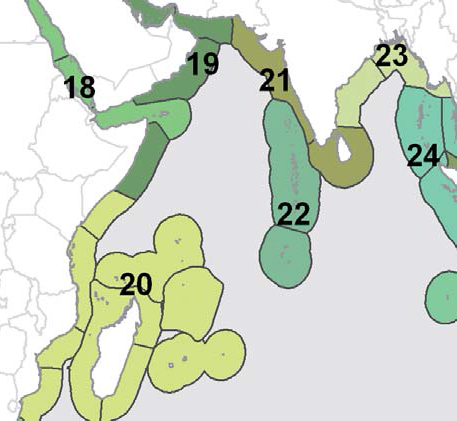

MEOW - Provinces within the West Indo-Pacific Realm. The Western Indian Ocean is # 20. MEOW - Provinces within the West Indo-Pacific Realm. The Western Indian Ocean is # 20.

© Spalding et al. 2007

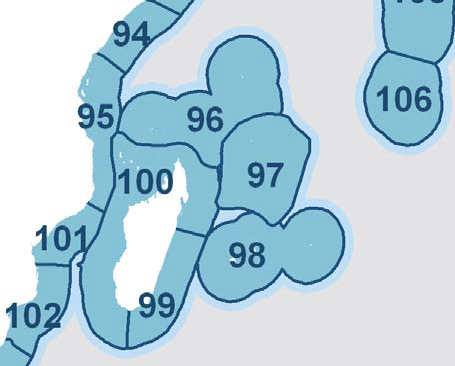

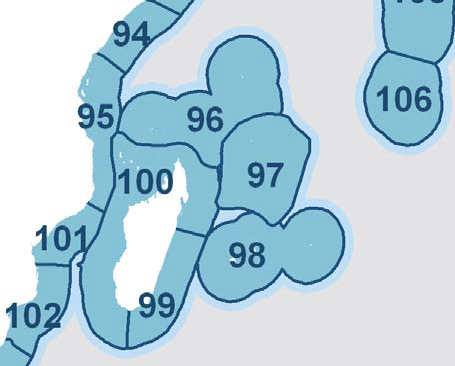

Ecoregions within the Western Indian Ocean, plus Chagos (#106) Ecoregions within the Western Indian Ocean, plus Chagos (#106)

© Spalding et al. 2007

|

Biodiversity and biogeography

Biogeography - The IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA), now the World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA), commissioned a study that together with a major text by Longhurst (1998) has laid the basis for recent marine biogeographic analyses. The East Africa (region 12) corresponds to the region more commonly known now as the Western Indian Ocean. In 2007 the Marine Ecoregions of the World (MEOW) classification scheme updated work done up to that point, dividing the world’s oceans into 12 realms, 62 provinces and 232 ecoregions.

In the MEOW scheme, the Tropical Indo-Pacific is divided into 4 realms – the West, Central and East Indo-Pacific, and the Eastern Pacific Realms. The West Indo-Pacific Realm extends from East Africa and the Red Sea to include the Andaman Sea and western Indonesia. Within it, the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) is recognized as a Province, and 6 smaller provinces are ranged along the Asian coastlines from the Red Sea to Thailand and Indonesia. Nine ecoregions within the WIO are proposed in the MEOW scheme. Within the WIO, conservation planning has been done for the mainland (WWF, 2004), and for the oceanic islands and Madagascar (RAMP-COI, unpublished), with the aim of identifying globally, regionally and nationally significant areas.

Biogeographic classifications are based on an area having a distinct fauna and flora, with unique features not found in other regions. The distinctness of the fauna and flora may relate to the geographic distributions of species, levels of species and genetic diversity and/or levels of endemism.

Drivers of biogeography - The distribution of species in the marine environment is driven principally by ocean currents, which themselves are constrained by geology. The four main oceanographic features of the WIO (see Features - Oceanography) identify the main patterns of species distributions to be found in the Province:

-

an Indo-Pacific fauna common across all tropical Indo-Pacific realms, carried on the South Equatorial Current from the center of biodiversity located in southeast Asia;

-

an Indo-Pacific fauna common across all tropical Indo-Pacific realms, carried on the South Equatorial Current from the center of biodiversity located in southeast Asia;

-

a high-diversity region in the northern Mozambique channel apparently related to the eddies that retain larvae there, the complex coastlines and its geological history;

-

decreasing diversity north and south as currents flow out of the northern Mozambique channel, with transitions towards the northern and southern extremes due to mixing with other water masses and climatic regions: in the north with the extreme environments and habitats in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Persian Gulf, and in the south, with the temperate systems off the Madagascar Plateau, South Africa and the southern Indian Ocean; and

-

relative isolation of the islands (Seychelles in the north, and the Mascarene islands in the south) in ocean gyres, resulting in distinct species assemblages and higher endemism due to their isolation. In the Seychelles, mixing with tropical provinces to the north results in a distinct fauna with mixed affinities. In the Mascarene islands, isolation from the SEC and the higher diversity ecoregions in the Mozambique channel, and no other adjacent tropical fauna to the south, results in higher levels of endemism.

Key aspects of biodiversity and biogeographic patterns relevant to the WIO are summarized here.

Species diversity -

Historically, species diversity across the Indo-Pacific region has been seen as one of generally linear decline in all directions from the high-diversity center in the southeast Asian region, or Coral Triangle, illustrated for corals by analyses up to the early 2000s that found decreasing diversity towards the African coast, with in some cases a higher peak of diversity in the Red Sea due to endemism. However recent reviews of the biodiversity literature note the exceptionally large gaps in species distribution records across the WIO and the Indian Ocean, such as on the East African coast. Thus, even today, prioritization exercises for conservation based simply on species counts should not be done without strong supporting evidence and ancillary information on ecology, oceanography and other processes that support biodiversity (see example in Features - Coral reefs).

Emerging evidence is showing that the northern Mozambique channel is a center of diversity for the WIO, very likely a result of high levels of connectivity due to the South Equatorial Current and Mozambique Channel eddies. Because the WIO may also have the highest diversity of the Indian Ocean (except for the Andaman Seas, which are faunistically more related to the Central Indo-Pacific Realm, or Coral Triangle), the northern Mozambique channel may be the second peak of shallow marine biodiversity in the world, after the Coral Triangle.

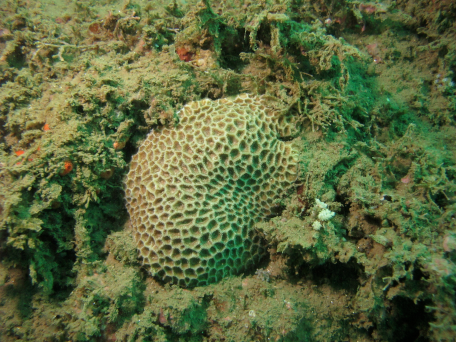

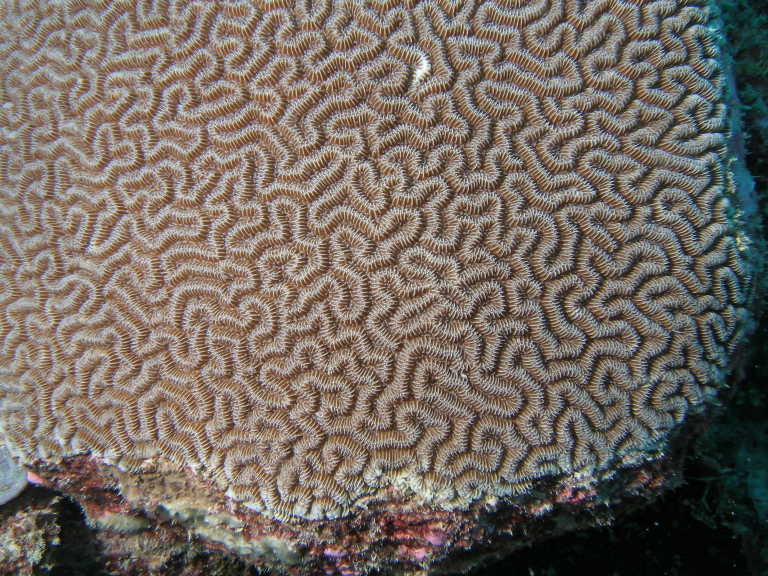

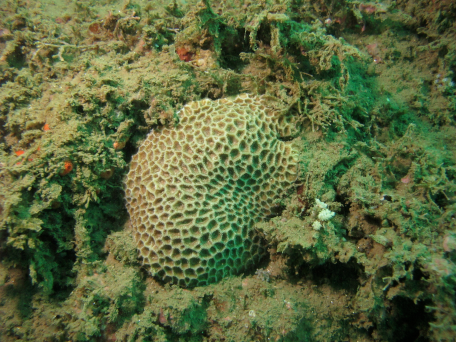

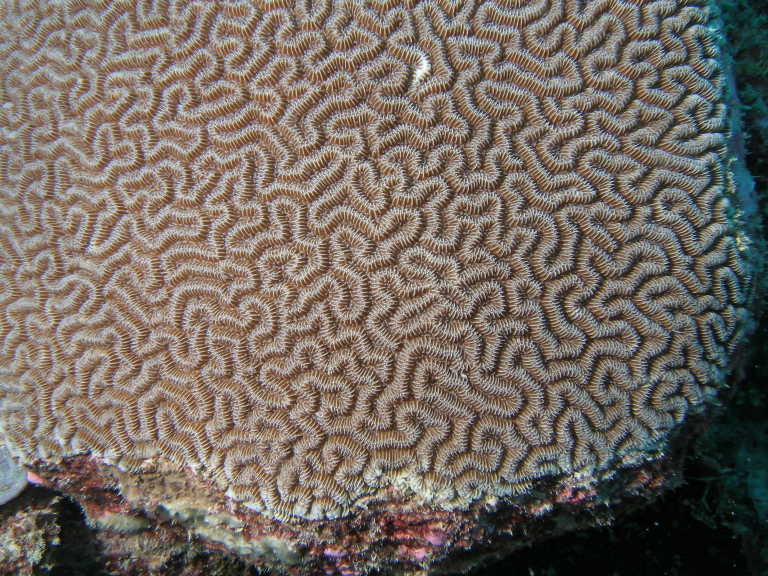

| Endemic corals in the WIO |

Anomastrea irregularis

|

Ctenela chagius

|

Physogyra lichtensteinii

|

|

Parasimplastrea sheppardi

|

Horastrea indica

|

| All photos: © David Obura

|

Endemism - In contrast to the high diversity core region in the Mozambique channel, regions with highest endemism tend to be highly isolated. The Mascarene Islands (Mauritius, Reunion and Rodrigues) in the southwest Indian Ocean are the most isolated of the tropical marine fauna of the WIO. They are south and east of the strong SEC and East Madagascar currents, and in a region that experiences intermittent currents in eddies that separate from those two currents, as well as return flow from southern Madagascar in the South Indian Ocean gyre.

The degree of endemism of reef fish in the Mascarene fauna is among the highest for reef fish, ranked fifth globally, comparable to levels reported for the remote island groups of the east part of the Pacific, such as the Hawaiian islands, the Galapagos and Easter/Pitcairn islands. Among 2086 reef fish known from the Indian Ocean, 25% are endemic. The highest level of endemism occurs in the Mascarene islands with 37 species endemic just to those islands out of a total of 819 species. Other reef taxa, particularly invertebrates, are too poorly sampled in the Indian Ocean to make meaningful regional comparisons. The life history of marine taxa is also important in understanding endemism – for example in the remote islands of the WIO there is a high percentage (70%) of hydrozoan species that lack the medusa stage in their life cycle, further contributing to high diversity through endemism.

| Endemic fish in the WIO |

Fusiliers of the WIO are still being described – here the widespread Pterocaesio marri and an unidentified species

|

Chaetodon interruptus – widespread Indo-Pacific butterflyfish showing Indian Ocean colour form.

|

| All photos: © Melita Samoilys

|

Ecotones - At the boundaries between major drivers of biodiversity processes, e.g. between provinces in the MEOW classification, and in some cases between ecoregions, the mixing of species from the different regions can result in unique and unusual species assemblages and habitats. Examples of these in the WIO include:

- the Seychelles islands, particularly in the north, with a transitional fauna with the northern Indian Ocean, including the Red Sea/Gulfs and south Indian and Sri Lankan coasts;

- the Northern Monsoon Coast in northern Kenya, with a transitional fauna between the main East Africa tropical zones, and the Somali-Arabian systems driven by cool nutrient rich upwelling;

- the South African, southern Mozambique and southern Madagascar faunas with a mixed fauna between tropical and temperate region.

Key References - Allen (2008); Carpenter et al. (2011); Faure (2009); Fricke et al. (2009); Gravier-Bonnet & Bourmaud (2006); Griffiths (2005); Kelleher et al. (1995); Longhurst (1998); Obura (2012); Obura (in review); Pichon (2008); RAMP-COI (unpublished); Richmond (2001); Roberts et al. (2002); Samoilys et al. (2011); Sheppard (1987); Sheppard (2000); Spalding (2012); Spalding et al. (2007); Veron (2000); Wafar et al. (2011); WWF (2004). --> References

|

MEOW - Provinces within the West Indo-Pacific Realm. The Western Indian Ocean is # 20.

MEOW - Provinces within the West Indo-Pacific Realm. The Western Indian Ocean is # 20. Ecoregions within the Western Indian Ocean, plus Chagos (#106)

Ecoregions within the Western Indian Ocean, plus Chagos (#106)